Our own results on flow prediction with diffusion models, and papers from other labs, e.g., for videos and climate models, make it clear that unconditionally stable neural operators for predictions are possible. In contrast, other works for flow prediction often seem to have trouble on this front, considering fairly short horizons (and observing considerable increases of errors over time). This poses a very interesting question: which ingredients are necessary to obtain unconditional stability, meaning networks that are stable for arbitrarily long rollouts? Are inductive biases or special training methodologies necessary, or is it simply a matter of training enough different initializations? Our setup provides a very good starting point to shed light on this topic.

Based on our experiments, we start with the hypothesis that unconditional stability is “nothing special” for neural network based predictors. I.e., it does not require special treatment or tricks beyond a carefully chosen set of hyperparamters for training. As errors will accumulate over time, we can expect that network size and the total number of update steps in training are important. Our results also indicate that the architecture doesn’t really matter: we can obtain stable rollouts with pretty much “any” architecture once it’s sufficiently large.

Interestingly, we find that the batch size and the length of the unrolling horizon play a crucial role. However, they are conflicting: small batches are preferable, but in the worst case under-utilize the hardware and require long training runs. Unrolling on the other hand significantly stabilizes the rollout, but leads to increased resource usage due to the longer computational graph for each NN update. Thus, our experiements show that a “sweet spot” along the Pareto-front of batch size vs unrolling horizon can be obtained by aiming for as-long-as-possible rollouts at training time in combination with a batch size that sufficiently utilizes the available GPU memory.

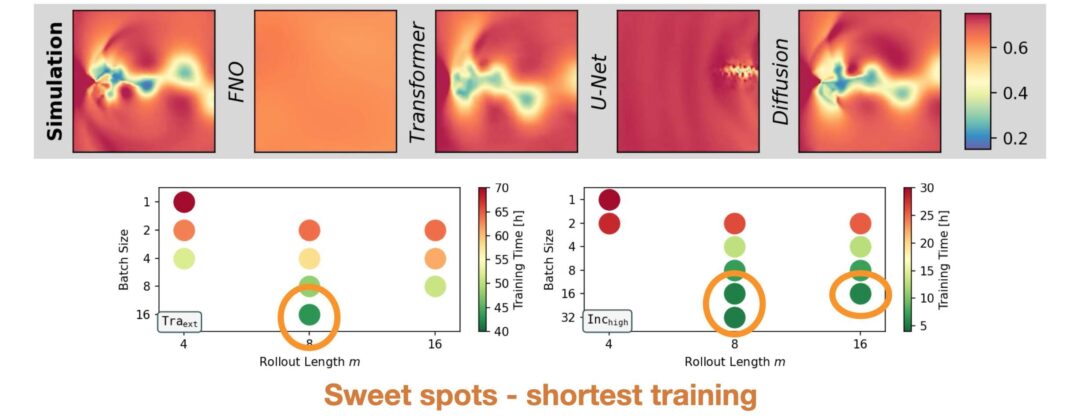

Learning Task: To analyze the temporal stability of autoregressive models on long rollouts, two flow prediction tasks from our ACDM benchmark are considered: an easier incompressible cylinder flow (Inc), and a complex transonic wake flow (Tra) at Reynolds number 10 000. For Inc, the models are trained on flows with Reynolds number 200 – 900 and required to extrapolate to Reynolds numbers of 960, 980, and 1000 during inference (Inchigh). For Tra, the training data consists of flows with Mach numbers between 0.53 and 0.9, and models are tested on the Mach numbers 0.50, 0.51, and 0.52 (Traext). For each sequences in both data sets, three training runs of each architecture are unrolled over 200 000 steps. This unrolling length is of course no proof that these networks yield infinitely long stable rollouts, but from our experience they feature an extremely small probability for blowups.

Architectures: As a first comparison, we train three model architectures with an identical backbone U-Net (as a representative of convolutional and discrete neural operators), that use different stabilization techniques. This comparison shows that it is possible to successfully achieve the task “unconditional stability” in different ways:

- Unrolled training (U-Netut) where gradients are backpropagated through multiple time steps during training.

- Models trained on a single prediction step with added training noise (U-Nettn). This technique is known to improve stability by reducing data shift, as the added noise emulates errors that accumulate during inference.

- Autoregressive conditional diffusion models (ACDM). A DDPM-like model is conditioned on the previous time step and iteratively refines noise to create a prediction for the next step. The resulting predictor is then autoregressively unrolled for a full simulation rollout.

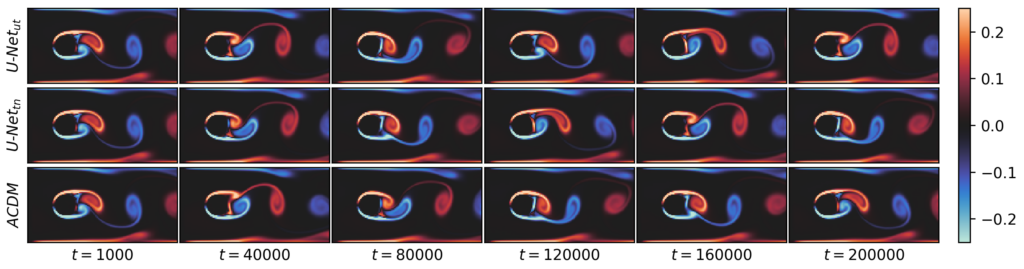

Figure 1: Vorticity predictions for an incompressible flow with a Reynolds number of 1000 (top) and for a transonic flow with Mach number 0.52 (bottom) over 200 000 time steps.

Figure 1 above illustrates the resulting predictions. All methods and training runs remain unconditionally stable over the entire rollout on Inchigh. Since this flow is unsteady but fully periodic, the results of all models are simple, periodic trajectories that prevent error accumulation. For the sequences from Traext, one from the three trained U-Nettn models has stability issues within the first few thousand steps and deteriorates to a simple, mean flow prediction without vortices. U-Netut and ACDM on the other hand are fully stable across sequences and training runs for this case, indicating a fundamentally higher resistance to rollout errors which normally cause instabilities. The autoregressive diffusion models turn out to be unconditionally stable across the board, so we’ll drop them in the following evaluations and focus on models where stability is more difficult to achieve: the U-Nets as representatives of convolutional, discrete neural operators.

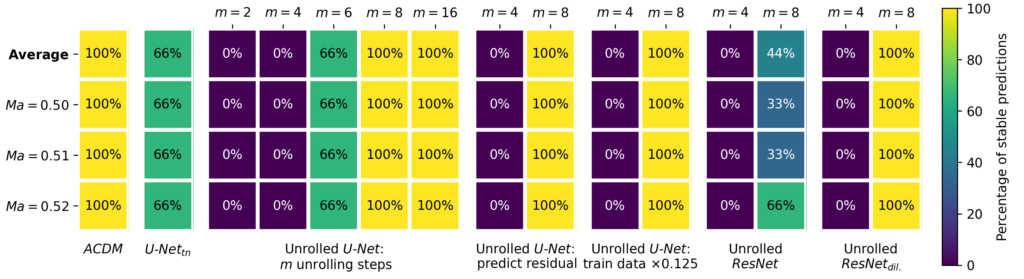

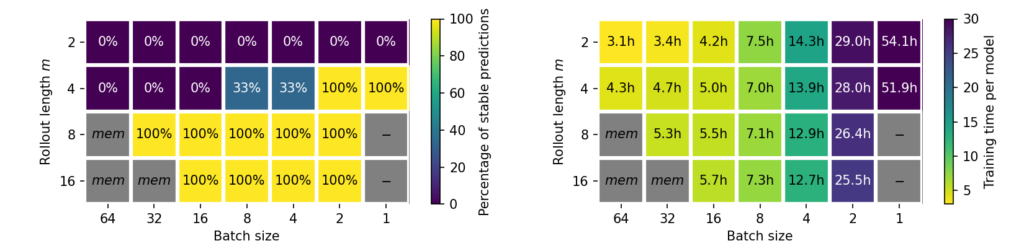

Stability Criteria: Focusing on the U-Net networks with unrolled training, we will next focus on training multiple models (3 each time), and measure the percentage of stable runs they achieve. This provides more thorough statistics compared to the single, qualitative examples above. We’ll investigate the first key criterium rollout length, to show how it influences fully stable rollouts over extremely long horizons. Figure 2 lists the percentage of stable runs for a range of ablation models on the Traext data set with rollouts over 200 000 time steps. Results on the indiviual Mach numbers, as well as an average are shown.

Figure 2: Percentage of stable runs on the Traext data set for different ablations of unrolled training.

The most important criterion for stability is the number of unrolling steps m: while models with m <= 4 do not achieve stable rollouts, using m >= 8 is sufficient for stability across different Mach numbers. Three factors that did not substantially impact rollout stability in our experiments are the prediction strategy, the amount of training data, and the backbone architecture. First, using residual predictions, i.e., predicting the difference to the previous time step instead of the full time steps itself, does not impact stability. Second, the stability is not affected when reducing the amount of available training data by a factor of 8 from 1000 time steps per Mach number to 125 steps (while training with 8× more epochs to ensure a fair comparison). This training data reduction still retains the full physical behavior, i.e., complete vortex shedding periods. Third, it possible to train other backbone architectures with unrolling to achieve fully stable rollouts as well, such as dilated ResNets. For ResNets without dilations only one trained model is stable, most likely due to the reduced receptive field. However, we expect achieving full stability is also possible with longer training rollout horizons.

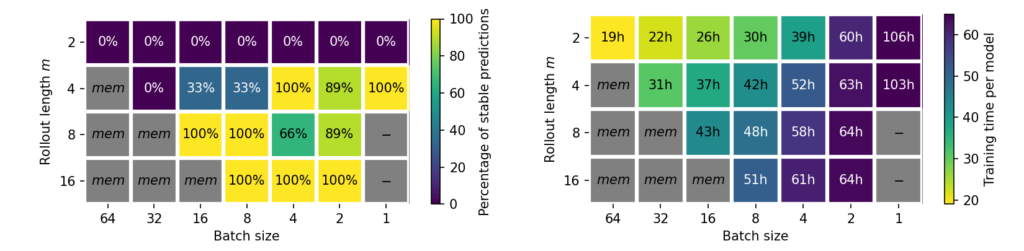

Batch Size vs Rollout: Furthermore, we observed that the batch size can impact the stability of autoregressive models. This is similar to the image domain where smaller batches are know to improve generalization, which is the motivation for using mini-batching instead of gradients over the full data set. The impact of the batch size on the stability and model training time is shown in Figure 3, for both investigated data sets. Models that only come close to the ideal rollout lenght at a large batch size, can be stabilized with smaller batches. However, this effect does not completely remove the need for unrolled training, as models without unrolling were unstable across all tested batch sizes. Note that models with smaller batches were trained for an equal number of epochs, as an identical number of network updates did not improve stability. For the Inc case, the U-Net width was reduced by a factor of 8 across layers to artifically increase the difficulty of this task, as otherwise all parameter configurations would already be stable.

Figure 3: Percentage of stable runs and training time for different combinations of rollout length and batch size. Shown are results from the Traext data set (top) and the Inchigh data set (bottom). Grey configurations are omitted due to memory limitations (mem) or due to high computational demands (-).

Increasing the batch size is more expensive in terms of training time on both data sets, due to less memory efficient computations. Using longer rollouts during training does not necessarily induce longer training times, as we compensate for longer rollouts with a smaller number of updates per epoch. E.g., we use either 250 batches with a rollout of 4, or 125 batches with a rollout of 8. Thus the number of simulation states that each model sees over the course of training remains constant. However, we did in practice observe additional computational costs for training the larger U-Net model on Traext. This leads to the question which combination of rollout length and batch size is most efficient.

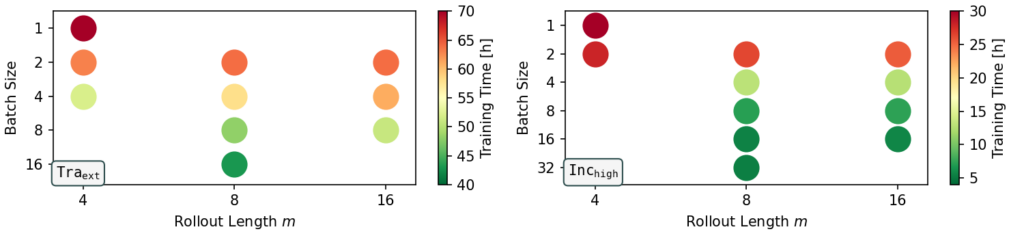

Figure 4: Training time for different combinations of rollout length and batch size to on the Traext data set (left) and the Inchigh data set (right). Only configurations that to lead to highly stable models (stable run percentage >= 89%) are shown.

Figure 4 shows the central tradeoff between rollout length and batch size (only stable versions included here). To achieve unconditionally stable neural operators, it is consistently beneficial to choose configurations where large rollout lengths are paired with a batch size that is big enough the sufficiently utilize the available GPU memory. This means, improved stability is achieved more efficiently with longer training rollouts rather than smaller batches, as indicated by the green dots with the lowest training times.

Summary: With a suitable training setup, unconditionally stable predictions with extremely long rollout are possible, even for complex flows. According to our experiments, the most important factors that impact stability are:

- Long rollouts at training time

- Small batch sizes

- Comparing these two factors: longer rollouts result in faster training times than smaller batch sizes

- At the same time, sufficiently large models are necessary, depending on the complexity of the learning task.

Factors that did not substantially impact long-term stability are:

- Prediction paradigm during training, i.e., residual and direct prediction are viable

- Additional training data without new physical behavior

- Different backbone architectures, even though the ideal number of unrolling steps might vary for each architecture

Further information on these experiments can be found in our paper https://arxiv.org/abs/2309.01745 and visualizations of trajectories with shorter rollout on our project page https://ge.in.tum.de/publications/2023-acdm-kohl/.